In the US, and around the world, men are often told to value strength, control, and self-sufficiency, and to avoid being vulnerable, or asking for help. Men’s displays of sadness, loneliness, affection, love, and friendship – rather than being recognized as authentic and necessary – are all too often interpreted as signs of weakness or a failure to be a “real man.”

The stories that are told, and the beliefs that are held, about how men should and shouldn’t behave, have serious implications for the lives of those socialized as men. Young men who believe in the most restrictive ideas about manhood – including that they shouldn’t be vulnerable or ask for help – are consistently more likely to binge drink, bully and harass, to show signs of depression, and to have considered suicide.

In her book Deep Secrets, researcher Niobe Way reveals that from a young age, boys do recognize the importance of close friendships and connection. Drawing from hundreds of interviews with adolescent boys in the US, she finds that boys share their deepest secrets and feelings with their closest male friends. Yet, as they move into adolescence, boys become distrustful, lose these friendships, and feel isolated and alone.

What is changing as boys grow up? Researchers and culture writers increasingly point to how rigid masculine norms influence the way boys and men think about their friendships, and how they go about seeking emotional support and connections.

“The problem with that for me is … because I was raised that way, I cannot break that, like even when I come on the verge of crying, nothing happens. I just sit there and get more mad at what is going on because I can’t break. It just forces [me] to go more internal and I can’t have that outlet.”

Focus Group Participant, Washington, DC, US (The Man Box: A Study on Being a Young Man in the US, UK, and Mexico)

What does our research say about the links between masculinities and asking for help?

1. Rigid ideas about “manhood” often characterize asking for help as a sign of weakness.

According to The Man Box, Equimundo’s study of young men ages 18 to 30 in the US, UK, and Mexico, these pressures about self-sufficiency and never seeking help are still very common in respondents’ lives. The majority of men in the US and UK reported that they’d encountered the social instruction that “A man who talks a lot about his worries, fears, and problems shouldn’t really get respect” and that “Men should figure out their personal problems on their own without asking others for help.” These messages can produce a fear of appearing vulnerable, which still has a powerful influence over young men’s behaviors, particularly for men in the Man Box. To recognize pain—physical or emotional—is to risk being told by your male friends or family that you’re not a “real man.”

2. When men do seek support, it is from the women in their lives.

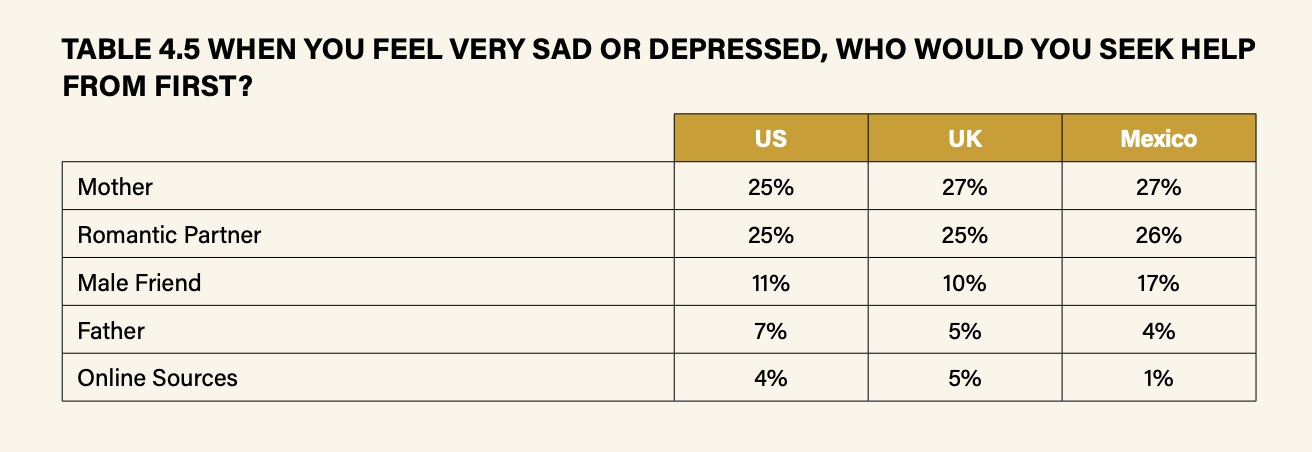

In line with the Man Box rule that men need to be self-sufficient, young men say they are more likely to provide emotional support to others than they are to be emotionally vulnerable or seek help themselves. When they do seek support, it is from women in their lives: their mothers, girlfriends, or wives. It is much rarer for young men to seek help from a male friend, and they almost never do so from their fathers.

3. Young men are eager for spaces to talk about their feelings, and to talk about gender, power, and their relationships with other men.

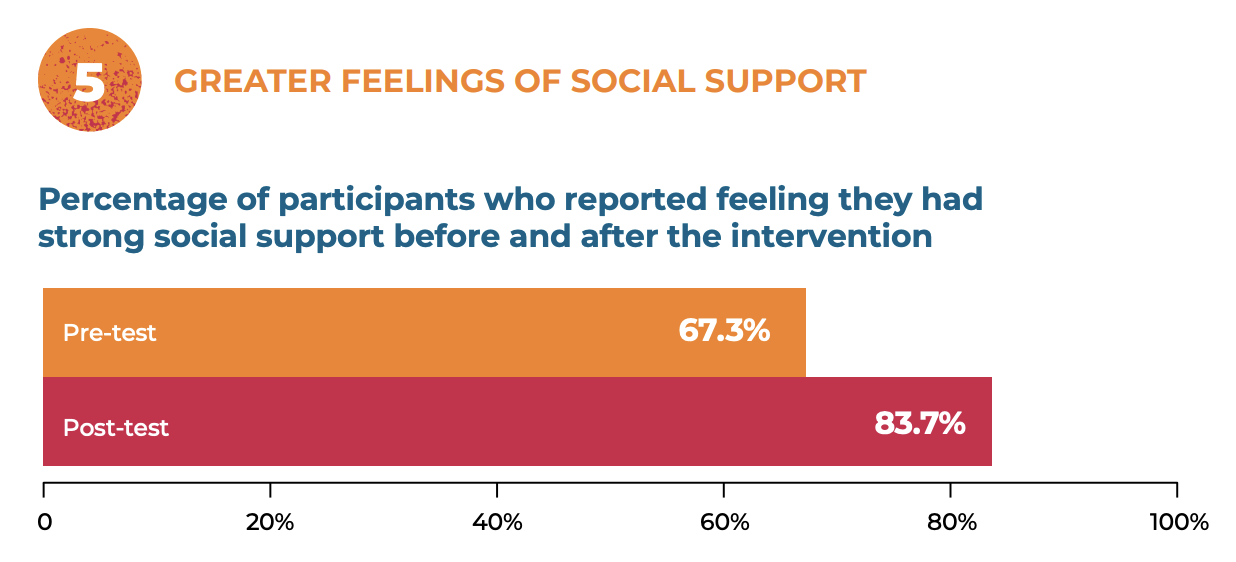

In a recent evaluation of Manhood 2.0, Equimundo’s interactive, 13-hour, seven-session curriculum focused on gender, power, relationships, consent and more, young men report that they valued having a shared, safe space to talk about their feelings and to break down gender stereotypes. Furthermore, Manhood 2.0 participants were more likely to report at post-intervention that they have someone they can go to when they feel sad, depressed, or stressed.

How can we shift our expectations of men’s social connections, and manhood more broadly?

Many of the behaviors society identifies with manhood, such as self-sufficiency, acting aggressive, and asserting control, are communicated from a very young age and throughout boys’ and men’s lives. How we raise our children, and which stories we choose to tell them about how they should be living their lives, has a huge impact on how they will embrace or reject gender stereotypes. For parents and for peers, this means we need to encourage and affirm boys’ and men’s vulnerability and ability to form and maintain connections. It means allowing and creating space for uncomfortable and critical conversations about what it means to be a man.

Resources, such as 9 Tips for Parents: Raising Sons to Embrace Healthy, Positive Masculinity produced by Equimundo in partnership with Plan International USA, provide evidence-backed guidance on how parents can navigate conversations on healthy masculinity, encourage self-expression, and support boys in becoming the best men they can be.