Tell us a bit about who you are and where you are based.

I’m a senior research officer at Equimundo, based in the Washington, DC area, and I’ve been with the organization for almost two years. During my time here, I’ve primarily been involved in formative and evaluation research for our projects in Latin America. So far, that has included partnering with local organizations to plan and evaluate fatherhood programs in Colombia and Paraguay and work on Global Boyhood Initiative (GBI) programs in Mexico and Bolivia. I’ve also worked on a research project exploring male allyship for gender equality in the workplace.

Your academic background centers on men’s mental health and psychosocial well-being. Why did you choose those topics?

Through my background in public health, I became very aware of the risks of vertical health programs that come into communities and impose a focus on a single health issue without listening to community priorities. I also became wary of efforts to reduce mortality at all costs, without thinking about quality of life, which is what brought me to work in mental health and psychosocial well-being promotion, which I try to view very holistically as promoting well-being, how ever that might be defined in a given context. For my PhD, I knew I wanted to focus on that topic, but more importantly, I wanted to take a participatory approach to doing the work.

Men’s mental health and well-being wasn’t necessarily a particular interest of mine at the time, but early in my PhD I got involved in a participatory project focused on women’s well-being in Guatemala through a colleague at McGill University. It was the women’s groups in the communities pointing to the need to work with men in order to address the key determinants of women’s well-being, including domestic violence and substance use in the home, that led me to build my PhD research around men’s mental health and well-being specifically.

Tell us about implementation science and your acting as a bridge between research and programs.

I’ve always been very interested in carrying out applied research – which means not just understanding gender norms and how they are affecting health and well-being, but performing research to understand what works to foster better outcomes. Implementation science takes this a step further to explore how we can put what works into practice – for example, research that focuses on adapting evidence-based programs for use in new contexts or their integration into health systems and policies.

Evidence-based programs are often seen as the key to achieving desired outcomes, but without sufficient attention to the factors that influence implementation–things like cultural norms, family structures, and the political context–the most effective program from one setting is unlikely to achieve the same results in a different setting.

Much of my role at Equimundo involves designing research to understand how we can adapt and implement evidence-based programming to fit the needs of families in different contexts, and building knowledge about what these programs can achieve, what works to implement these programs, and what we can do better. For example, I’ve been working on a project in Colombia to understand how Equimundo’s Program P, which proved effective for increasing men’s engagement in caregiving and reducing their use of violence toward partners in rural Rwanda, can be adapted for fathers in urban Bogotá.

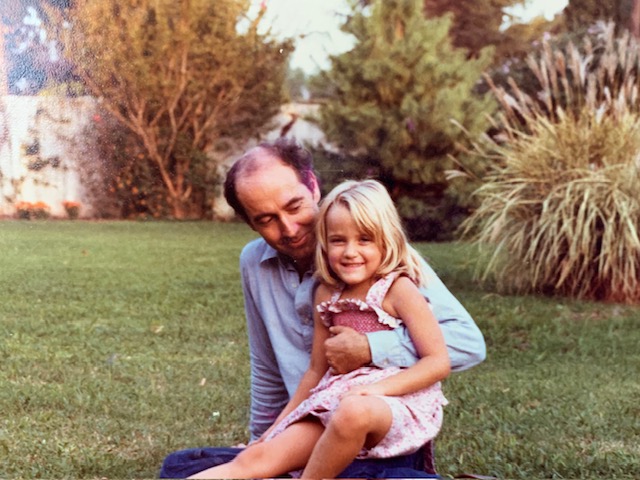

What does family life look like for you, and are there any connections between the work you do and what happens in your home life?

There are so many! I’ll focus on two… the first is the fact that since entering this field I’m now a mom of two young boys. As someone thinking a lot about promoting psychosocial well-being, I see so many ways that the gender norms imposed on boys – the social pressure they experience to suppress their feelings, not show vulnerability, and not have close, affectionate friendships – make it really hard for them to thrive psychosocially and also contribute to the thriving of those around them. As Ruth Whippman put it in her recent New York Times essay, “Under patriarchy, boys and men get everything, except the thing that’s most worth having: human connection.”

I’m constantly thinking about how I can support my own kids to recognize and challenge the norms imposed on them while I’m simultaneously carrying out research for our Global Boyhood Initiative that’s focused on these same goals in other contexts and on a larger scale.

My experience with my own sons gives me insight into how we can conduct research and plan programs to address these topics, and the research and programs I work on frequently give me ideas for how to talk to my kids and make decisions about the types of activities I expose them to. The work also helps me identify what’s missing in our communities to support boys and gives me ideas for how to foster better boyhoods in my own community.

Second, as someone who wants to be very involved as a parent and also pursue a meaningful career, I’m constantly witnessing the ways that our work lives and social support systems aren’t set up to allow parents, particularly women, to thrive in both their careers and their caregiving. I feel a deep connection between the personal struggles I’ve faced in searching for that balance, and our advocacy/programmatic work that strives to create more caregiver-friendly policies and workplaces.

You’re currently working on projects for GBI. Which GBI resources have you enjoyed using with your children?

I build many of the Action Steps for Parents into how I talk to my boys about gender. When my kids were very young, it felt possible to shelter them from some of the rigid messages out there about what boys should be like and expose them to the toys, activities, and role models that might counteract those stereotypes, but as they’ve gotten older I’ve realized these messages are everywhere and it’s most important to give them the tools to recognize and question them.

You’re also working on some of our fatherhood projects. What would you say is the most valuable lesson you’ve learned in designing programs for dads?

It’s so hard to get men to show up when they are seen as only having an instrumental role in women’s and children’s lives. We must do better at listening to men and boys and allowing them to participate in planning programs that work for them and that engage with them in ways they want to engage –– that address both their own needs and desires while also their role in promoting the well-being of the whole family.

We also hear so often from dads who want to have a more active role in caregiving but face many structural barriers like long working hours at informal jobs. Programs that target individual men and families will never work on their own. If we want dads to step up to these caregiving roles, we must continue working to address the policies and structures that can support them to take on a more active role in caregiving.