Originally distributed by the New York Times/Hearst News Service, May 2006

“Will you PLEEEEEASE be my Daddy?” asked 10-year-old Rodney, tugging on my shirtsleeve and looking up at me with imploring eyes.

I met Rodney only 45 minutes earlier during a small focus group I conducted in his school. The focus group was part of my research for a book I am writing on daddying. I coined the term daddying to differentiate the one-time biological act of fathering, requiring no more commitment than some DNA, from the lifelong process of daddying, requiring a lifelong commitment.

The melancholy, unfocused look in Rodney’s eyes brought something important into focus for me. I had seen this look of yearning before, and it always yanked at my heart. I had seen it in the eyes of other kids I had spoken with, as well as in the eyes of fathers and grandfathers I interviewed.

Suddenly I recalled seeing that combination of yearning and resignation somewhere else. I had seen it staring back at me in a mirror long ago, reflecting my thoughts of what might have been if circumstances had been different – if, for instance, my dad had been more present when I was growing up. Although I knew he would be there in a pinch, I needed more than a pinch of his attention.

As often happens when we do not get what we need at home, I looked elsewhere. I began to create the “ideal dad” in my mind’s eye, gathering paternal qualities I admired from other men: a stranger, who winked at me across the aisle on a city bus; the Good Humor man, who allowed me to be his “assistant” as he sold ice cream outside my elementary school; my fifth grade teacher, who was the kindest man I ever met; my grandfather, who was sensitive as he occasionally helped me with some of my high school homework; a local college baseball player, who invited me to be the team bat boy; a friend’s dad, who had a playful sense of humor; an uncle, who once came to watch me play in a high school soccer game; and the director of a camp for children with emotional disorders, who was a supportive mentor during the three summers I served as a counselor.

I even gathered qualities from bits and pieces of characters I read about in books or saw in movies or on television. Without a conscious awareness, I was creating a patchwork dad to provide the warmth I needed and to mend the emotional holes created by a largely absent father.

I scavenged daddy morsels wherever I could find them to satisfy my hunger for paternal attention. My daddy-deprivation also caused me to look within, to daydream about ways I would be a different kind of father. I made a youthful commitment to be exuberantly involved in the lives of the children I planned to have some day.

During the 60 years of my life when my father was still alive, I had rationalized that he was as good a dad as he knew how to be; that he never learned how to be a more present dad because his father was absent most of his life. I rationalized that expectations for men in the 1940s and ’50s were different from today: fathers then were not expected to be much more than breadwinners and disciplinarians. Nurturing was considered a mother’s job, not something you expected of dads. But all my rationalizing did little to lessen the sadness I felt.

Twenty years ago, when one of my four-year-old students told me that he saw my role as school principal as being “the daddy of the school,” I realized that one of the reasons I had chosen a career that involved daily contact with kids was to do what I could to minimize the hurt that many children feel as a result of an adult male attention deficit – the deficit of attention that too many kids receive from their fathers.

Although there are things we do not know about good daddying, a lot can be learned by simply asking kids, fathers, and grandfathers themselves – that is what I did during thousands of interview hours in 17 cities in three countries. I also learned that daddy-yearning cuts across generations, has a cumulative corrosive impact that stunts our fullest development, and that it can be minimized – if not prevented – with modest effort. I learned that the qualities kids said they want in a dad match the parental qualities dads said they most want to cultivate, and that those qualities are also the ones that child development professionals identify as important to enable children to thrive.

Above all, kids want their fathers to:

- Be there, really be there – not distracted by TV or other diversions (kids often described what I call “AWOL Fathers” – fathers who are absent without leaving)

- Take them as seriously as they take themselves

- Respect them, even if their dads don’t agree with them

- Set fair and consistent limits

- Demonstrate a sense of humor

- Provide affection

- Trust them

- Offer recognition

- State parental expectations unambiguously

Almost forty years ago I learned that when you become a dad your identity is changed forever. Although it may have taken a few years to realize, becoming a dad was the most transformational event in my life; it has been one of life’s rare opportunities to make a direct connection to my heart and my soul.

In our increasingly complex and scary world, kids and their parents need each other more than ever. It makes powerfully good sense to consider incorporating these desirable qualities into our parental behavior.

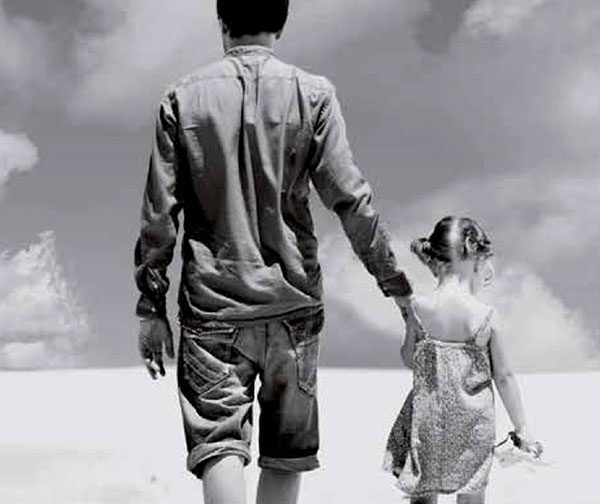

Each of us can decide whether to embrace this opportunity to really be there with the knowledge that our decision will echo through generations – because sometimes there is a roughness to the world that only a daddy can smooth out.

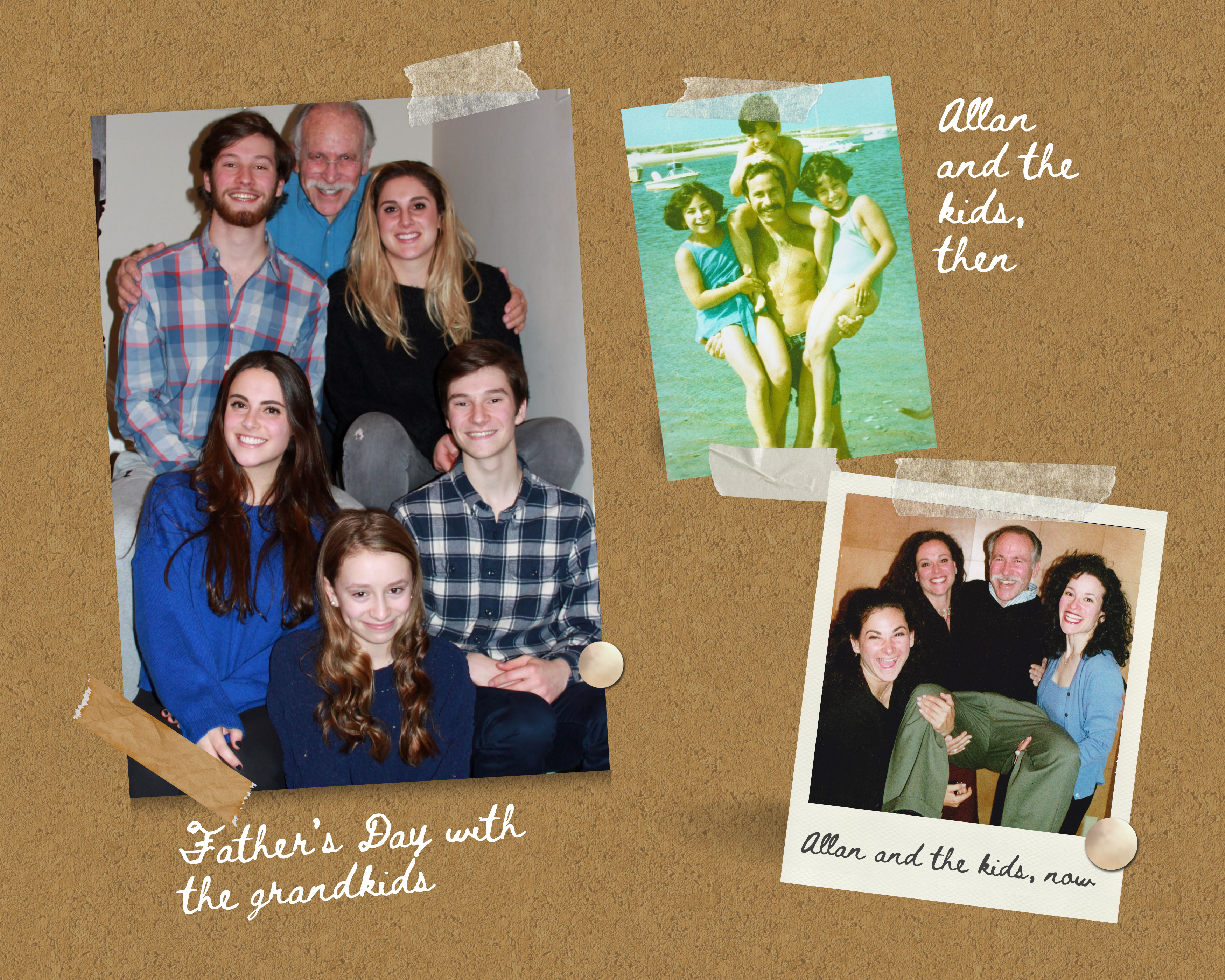

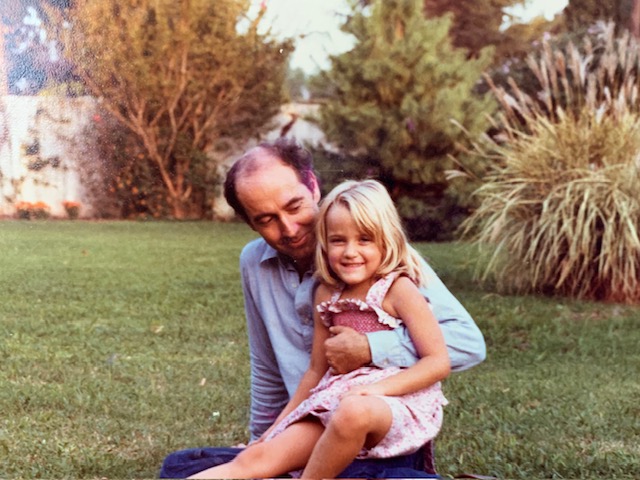

Allan Shedlin has devoted his life’s work to improving the odds for children and families. He has three daughters, five grandchildren, as well as numerous “bonus” sons, daughters, and grandchildren. Trained as an educator, Allan has alternated between classroom service, school leadership, parenting coaching, policy development, and advising at the local, state, and national levels. After eight years as an elementary school principal, Allan founded and headed the National Elementary School Center for 10 years. In the 1980s, he began writing about education and parenting for major news outlets and education trade publications, as well as appearing on radio and TV. In 2008, he was honored as a “Living Treasure” by Mothering Magazine and founded REEL Fathers in Santa Fe, NM, where he now serves as president emeritus. In 2017, he founded the DADvocacy Consulting Group. In 2018, he launched the DADDY Wishes Fund and Daddy Appleseed Fund. In 2019, he co-created and began co-facilitating the Armor Down/Daddy Up! and Mommy Up! programs. He has conducted daddying workshops in such diverse settings as Native American pueblos, veterans’ groups, nursery schools, penitentiaries, Head Start centers, corporate boardrooms, and various elementary schools, signifying the widespread interest in men in becoming the best possible dad. In 2022, Allan founded and co-directed the Daddying Film Festival & Forum (D3F) to enable students, dads, and other indie filmmakers to use film as a vehicle to communicate the importance of fathers or father figures in each other’s lives. Call for Entries for the 4th annual D3F in April 2025 will begin on November 18, 2024. Allan earned his elementary and high school diplomas from NYC’s Ethical Culture Schools, BA at Colgate University, MA, at Columbia University’s Teachers College, and an ABD at Fordham University. But he considers his D-A-D and GRAND D-A-D the most important “degrees” of all.