65%

of young men between the ages of 18-23 say that “no one really knows me well.”

Men’s mental health matters for everyone: for men themselves; for women, who generally bear the burden of care for male partners and sick and disabled men; for children, who can experience adverse outcomes from the poor health of caregivers; and for societies, which bear the social and economic cost of men’s mental illness and premature death. Poor mental health affects men’s mobility, productivity, and overall quality of life. The loss of a husband, father, son, or brother can also have lasting psychological, financial, and social effects on families and communities.

Deteriorating mental health for men has been associated with a crisis of connection. Stereotypical norms of masculinity – what we call the man box – place value on aspects of being male that encourage men to be independent, autonomous, stoic, strong, virile, and aggressive. These cultural expectations from men and boys are at the heart of why researchers are reporting higher suicide rates among men than women, report fewer close social ties than women, are lonelier and more isolated, have a higher prevalence of drug use than women and more externalizing problems.

Men’s poor health can have a long-lasting and profound impact on those around them, but can also have significant economic impacts on those who care for them, their families, and the whole economy. Women are generally responsible for picking up the pieces of men’s poor health or premature death, which create greater care and income-generation burdens for women.

Many barriers, including stigma and a lack of health literacy, are preventing too many men from seeking help for their mental health. And when men do seek help, the health system does not always respond to their needs. Research has shown that mental health providers may miss or misdiagnose psychological problems in men because of their own gender biases, believing that men simply need to “man up” and stop showing weakness, or that the symptoms they present are not consistent with diagnostic tools.

Our research shows that, in some settings, men who are more involved as fathers and caregivers are more likely to have better health, suggesting that the care of others may also support an ethic of self-care.

Told to “man up” or “be a real man,” men and boys who cannot meet the impossible, overlapping standards of toughness, self-sufficiency, dominance, and stoicism have their very identity withheld from them, with huge impacts on the quality of their interpersonal relationships, physical health, mental health and happiness, and longevity.

Through the Global Boyhood Initiative and our Many Ways of Being curriculum, our work aims to improve men’s healthy relationship skills and emotional connection. We believe healthy masculinity means men confidently owning their identity as caring, emotionally connected, cooperative people.

From the increased social acceptability of men in acknowledging mental health needs to the growing power in calling attention to men’s health, we have templates and approaches for making health services more inviting and better attuned to men’s diverse and intersectional mental health needs. Even as society makes mental health services more accessible, many men will resist this medical orientation. We must build into family and community life, throughout boyhood, an acknowledgment of the inescapable human need to be heard.

The leading health-risk behaviors that account for a major share of men’s ill mental health are directly related to masculine norms and masculinities interacting with other factors. These ‘traditional masculine norms’ can be protective of health in certain contexts (e.g. many men’s interest in physical fitness and diet), whereas they can also harm men when applied rigidly in others.

For example, men with symptoms of depression and strong conformity to traditional masculine norms are significantly less likely to access mental healthcare. Even after accounting for pregnancy and related care, men seek health care for physical and mental health concerns less frequently than women. This is a consistent trend across a diverse set of health concerns, through formal and informal outlets, and among men of different ages, nationalities, and races. Further, studies have shown that men who do seek care ask fewer questions and have shorter consultation times than women.

of young men between the ages of 18-23 say that “no one really knows me well.”

of men show depressive symptoms.

of men had thoughts of suicide in the prior two weeks; younger men show the highest levels of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation.

Men aged 18 to 23 have the least optimism for their futures and the lowest levels of social support.

Source: State of American Men

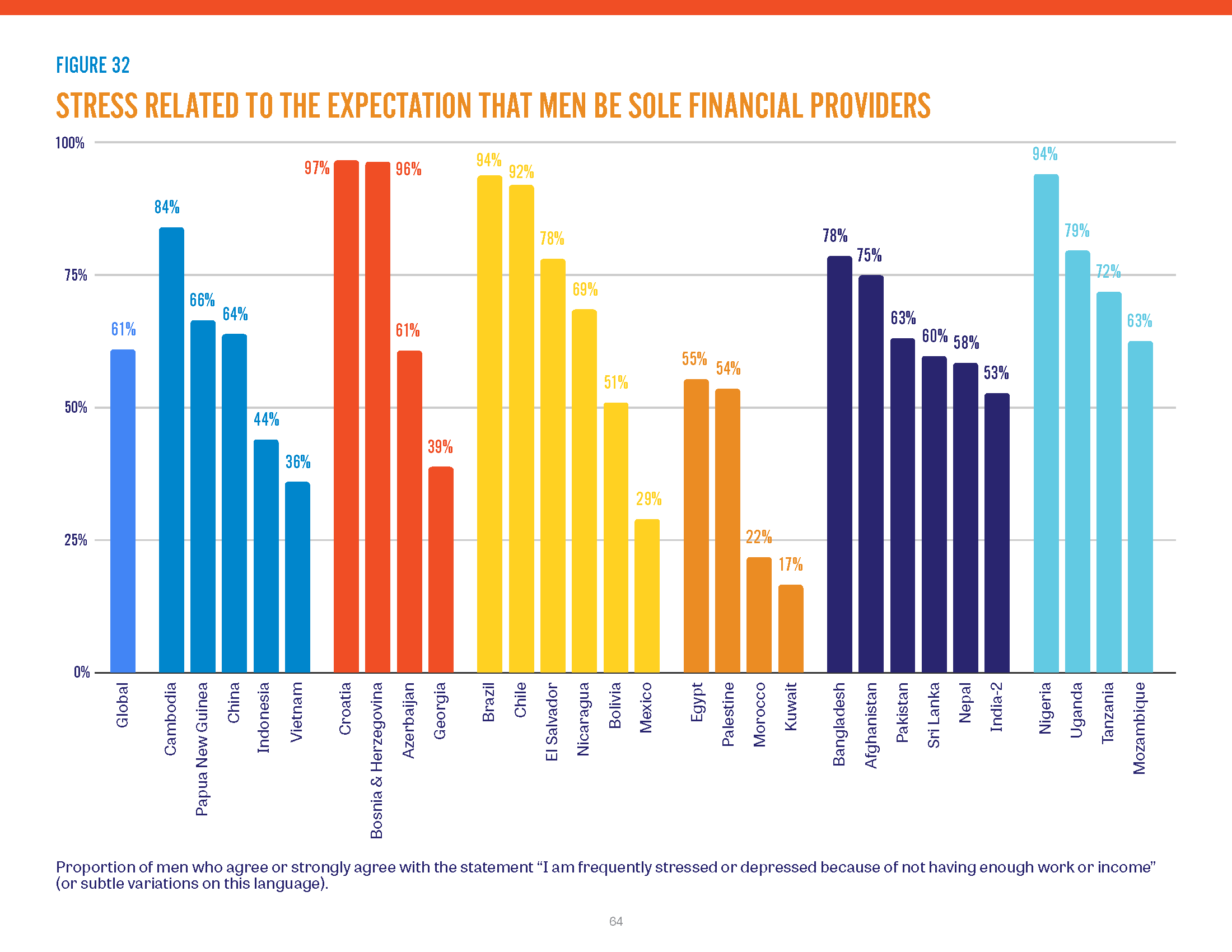

Findings from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES) related to mental health

The societal expectations that men should be breadwinners are strong and pervasive. Men often pin their identities on this financial provider role, but in many economic circumstances, this is impossible. Men face pressures to conform to this role from peers and family, including intimate partners, and their ability to fulfill the role can determine their eligibility for marriage and their satisfaction and stability within that marriage. Men perceive this pressure to be providers even in divergent settings with financial crises, war, displacement, or high unemployment rates. Although the “provider” identity is expected of all men, structural forces outside their control often curtail their opportunities to fulfill the role. A complementary aspect of traditional masculinity is that a man must be the “protector” of his family. In the midst of active political or armed conflict, the forces that risk the safety and livelihood of men and their families go far beyond anything under individual control. For example, over 95 percent of men and women in Palestine and Lebanon express worry about their families’ safety. War, economic instability, and other major structural factors continue to shape men’s lives in extremely diverse contexts and make it difficult for them to achieve their desired roles as providers.

Source: International Men and Gender Equality Survey Global Headlines report (2022)

The difference in life expectancy between men and women in the US is widening, with men now dying on average six years before women. Much of the gap is driven by men’s disproportionately higher rates of suicide and drug overdose—what have been called “deaths of despair.”